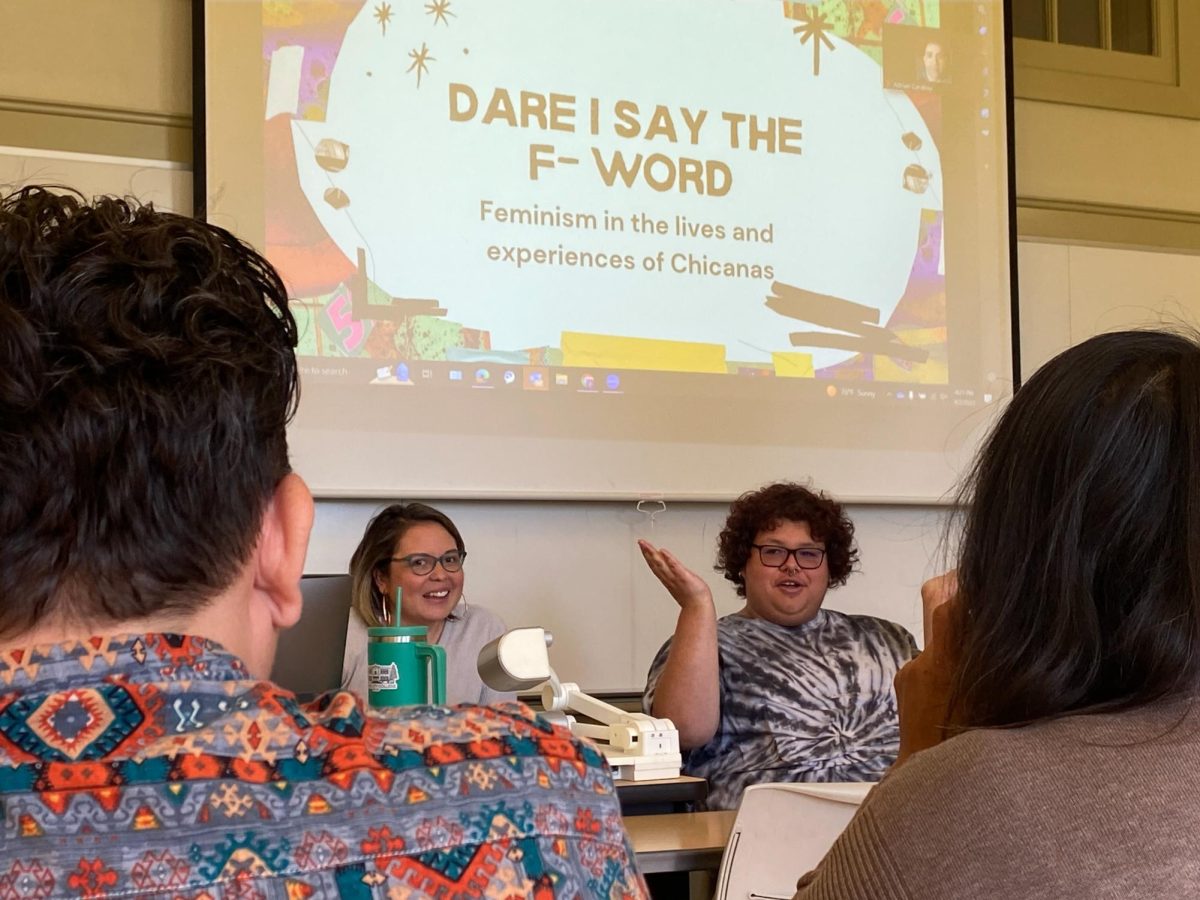

On April 2, an educational dialogue on the topic of Chicana feminism and oppression was initiated by Dr. Victoria Benavides, and the discussion lasted for over an hour.

Room 131 of the Old Administration Building was loud and lively even before the presentation began, with handshakes, hugs and laughter served everywhere. At 3:10, the coordinator for the International Student Service Program, Jesus Delgadillo, calmed the room and introduced the two speaking guests of honor.

Victoria Benavides is a faculty instructor who teaches cultural, ethnic and women’s studies on campus. As a devoted educator and mother, Benavides has a layered understanding of Chicana history and a passion for social justice.

“My mission is to work to achieve social justice at large, and ethnic studies is one of the best ways of opening that door into a bigger, better future,” Benavides said.

Delgadillo also introduced Noah Sanchez, a current student at FCC majoring in Chicano-Latino Studies, who worked with Benavides to organize the informational slideshow.

Intersectionality (how the effects of multiple forms of discrimination intersect) and PRAXIS (practical application of a theory, according to Merriam-Webster) were major focuses of the slideshow. PRAXIS feminism applies to a feminist action that actively changes and/or benefits the women’s surroundings as opposed to just thinking about the change and its implications.

After a group icebreaker that prompted the audience to meet table partners and swap stories, Sanchez began by overviewing the Chicana Feminist movement in the 1970s and 1980s. He explained how these were the formative years of the movement and how those activists were among the first to voice discontent with the labels bestowed upon them.

Ever since those early days, feminism has been looked at as a reactionary response to oppression.

“We really wanted to stress that Chicana feminism is much more than a reaction to a comment at a social event or oppression in everyday life. It doesn’t mean that you need to call out everything that happens to you, but you need the strength to talk about it with someone,” Sanchez said.

Not everyone in the room was Chicana, but all were able to chime in with their own personal perspectives and relate to one another through their shared struggles.

An audience member asked the panel how the LGBTQIA+ community interacts with Chicana feminism, and Benavides responded with a story about her time growing up.

Benavides began by explaining there are still entire Hispanic and Latinx communities that continue to deny and silence LGBTQIA+ voices. She was raised around people who heard feminism as a dirty word, thought it was “a white’s idea,” and thought that if a Chicana is a feminist, she’s been assimilated.

“It wasn’t until I went to college that I began to understand that feminism moved beyond just ideas of assimilation, that there is an entire women of color feminist movement. When I first told my mom that I thought she was a feminist, she didn’t want to hear it. But over time, I’ve gotten her to say, ‘maybe,’” Benavides recalled.

At 3:40, every listener/participant was asked to write a private note to a Chicana they knew that would benefit from listening in to the discussion or a Chicana who has already engaged in PRAXIS feminism.

This writing exercise gave everyone an opportunity to reflect on the important female figures, and specifically, Chicana figures in our lives. Once the allotted time ran by, people were encouraged to read their letters.

Some wrote to friends, but most who spoke up wrote to family. Auguste Kouadio, a professor in the African-American studies department, recited a letter written to his mother, “and through my mother, all women with brown skin,” Kouadio said.

The event forced everyone to ask important questions about the prejudiced world and answer them alongside complete strangers. This kind of discussion does not end after two hours and a slideshow, but we must all do our part to keep it ongoing, for the sake of every silenced voice throughout history.